Everything but commentary

Have you heard the good word of our lord and saviour Bayes?

Bayes' Theorem

Bayes' TheoremEpistemic status: not always very precise. The purpose of this blog post is to introduce the many sides of Bayesian probability theory that I have come across over the past few years. I used to be quite confused about this topic, and I feel less confused now, so hopefully this will be helpful to someone. I intend to expand on some of these topics in future posts.

The tagline of one of my favourite blogs - Astral Codex Ten, previously Slate Star Codex - reads:

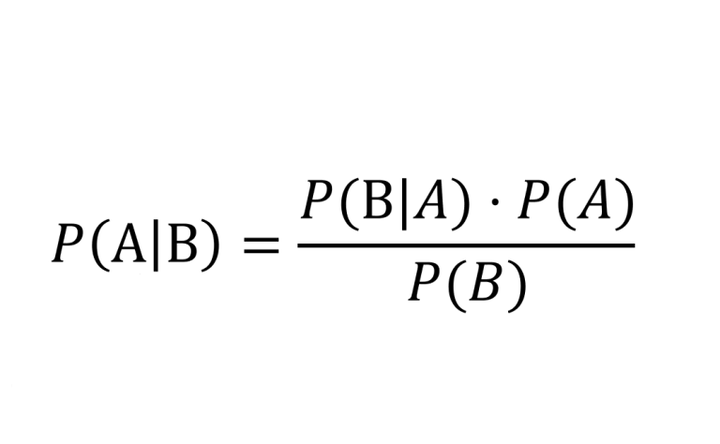

P(A|B) = [P(A)*P(B|A)]/P(B), all the rest is commentary.

This equation, more legibly written $p(A|B) = \frac{p(A) p(B|A)}{p(B)}$, is known as Bayes' theorem. Writing the theorem down is very easy, and proving it is not much harder - it’s a direct consequence of the product rule of probability theory. As early as the 18th century it was used by its namesake Reverend Thomas Bayes to solve a simple statistics problem. All in all, it doesn’t sound that groundbreaking. So what’s with this assertion that all the rest is commentary?

Representing beliefs

To understand that, we have to take a closer look at probability theory, and in particular at the many varied interpretations of probability itself. At the risk of simplifying an age-old debate, there are two widely held views on this matter: the frequentist view, and the Bayesian view.

The frequentist views probabilities as limiting frequencies: if a coin has a probability of 0.5 to land heads, then this is a statement about what happens if the coin is flipped a large number of times - the frequentist expects to see heads half the time. This is the view that is (or was) typically taught, and it works very well when the objects of study are those that have limiting frequencies we can sensibly talk about.

The Bayesian views probabilities as representations of knowledge: if a coin has a probability of 0.5 to land heads, then this is a statement about the Bayesian’s belief or knowledge of this coin. Like the frequentist, the Bayesian too expects to see heads half the time in a large number of flips, but - in contrast to the frequentist - can also make probabilistic statements about events that do not have natural limiting frequencies (e.g. ‘what is the probability that there is other intelligent life in our galaxy?').

Now note that a Bayesian who is really good at flipping coins, might be able to make the coin come up heads more often, e.g. 80% of times. If we learned this, we would assign a probability of 0.8 to the coin coming up heads - rather than 0.5 - without having seen any actual coin flips: our belief has changed our probability assignment. This gives us some indication that we’re reasoning as Bayesians in our daily lives (this indication might be deeper than expected).

Plausible inference

We can take this further, and imagine designing a robot that flips coins such that they always come up heads. Hypothetically, we would need to take many factors into account to do so: the mass of the coin, the force with which the robot flips, the density of air (or perhaps the positions and velocities of individual molecules), the elasticity of the surface the coin lands on, etc. If we manage this, we’ve now created a robot that flips a coin such that it deterministically lands heads: we no longer need probabilities to describe our state of knowledge about the coin.

This makes sense in the Bayesian framework, since probabilities were never meant to represent ‘randomness’ in a system: it was already about our state of knowledge. In the Bayesian framework, probabilities arise due to a lack of complete information about a system: if we had complete information of the factors influencing the coin flip, we could ‘simply’ calculate the result of the experiment, using the known laws of physics (and if we obtain the wrong result we learn that our information was incomplete, our measurement apparatus is not precise enough, or we’re wrong about the laws of physics).

Alright, so the Bayesian framework makes sense if we have complete information: what about if we don’t? Cox’s theorem provides a theoretical justification for (objective Bayesian) probability theory as a general theory of plausible inference. This means that we can use Bayesian probability theory to reason under incomplete information, exactly as suggested by referring to probabilities as representations of knowledge. Bayes’ theorem tells us how to do inference correctly and consistently: all the rest is commentary.

This point is belaboured by E.T. Jaynes, who advocates an interpretation of probability theory as extended logic (i.e. extending logical deduction to reasoning under uncertainty). Full disclosure: I am quite partial to this interpretation.

Back to the theorem

By this point one might wonder: if Bayesian probability theory tells us precisely how to do inference correctly, why use other methods at all? The facetious answer is that we don’t: it is after all a widely known and indisputable fact that all inference methods are special cases of Bayesian inference.

The more reasonable answer is that true Bayesian inference is really hard, and actually quite infeasible in practice. Let’s return to the theorem to see why.

The statement $p(A|B) = \frac{p(A) p(B|A)}{p(B)}$ encodes the following intuition: updated belief = prior belief + new information. If I start out believing a coin is fair, and then I observe a very unlikely string of 20 heads in a row, I am going to no longer believe the coin is fair. And the magic: Bayes' theorem tells me exactly how much I should no longer believe that, i.e. how much I should update my belief.

Bayesians call the updated belief the posterior, the prior belief the prior, and the new information the likelihood1. And of course, the next time you do inference, your previous posterior is your current prior.

With this, we identify $p(A)$ as the prior belief that $A$ is true, $p(B|A)$ as the likelihood of observing data $B$ if $A$ is true, and $p(A|B)$ as the posterior belief in $A$ after observing $B$. The denominator $p(B)$ is called the evidence2 for $B$, which is mostly treated as a normalisation factor. Note that by taking the logarithm on both sides, we indeed obtain something of the form: updated belief = prior belief + new information.

To apply the theorem, we need to think about what $A$ and $B$ represent in practice. Typically, we think of $A$ as an hypothesis about the world: e.g. some process that we’re trying to describe. The data we observe about this process can be identified with $B$. Let’s denote the hypothesis as $\mathcal{H}$ and the data as $\mathcal{D}$, so Bayes' theorem becomes:

$p(\mathcal{H}|\mathcal{D}) = \frac{p(\mathcal{H}) p(\mathcal{D}|\mathcal{H})}{p(\mathcal{D})}$.

We can now sensibly talk about inference: starting with some distribution over hypotheses $\mathcal{H}$ representing our prior beliefs, we observe data $\mathcal{D}$, which in turn causes us to update our beliefs to a new distribution over the same hypotheses $\mathcal{H}$.

Prior information

To start using the theorem, we need to specify our prior information $p(\mathcal{H})$: how likely do we think $\mathcal{H}$ is a priori - for instance, if $\mathcal{H}$ is the hypothesis that the coin is fair? Well, this depends on what information we already have about the coin (and the person flipping the coin, and any other relevant information). Probability theory as extended logic prescribes using all the (relevant) available information when doing inferences: if I happen to know the coin has heads on both sides, I should definitely include this information.

So let’s call any relevant information $\mathcal{I}$, and restate Bayes' theorem:

$p(\mathcal{H}|\mathcal{D}, \mathcal{I}) = \frac{p(\mathcal{H}|\mathcal{I}) p(\mathcal{D}|\mathcal{H}, \mathcal{I})}{p(\mathcal{D}|\mathcal{I})}$.

Ah, much better. So we just need to specify all possible hypotheses $\mathcal{H}$ consistent with our prior information $\mathcal{I}$, observe data $\mathcal{D}$ (e.g. do experiments), compute $p(\mathcal{D}|\mathcal{I})$, and then $p(\mathcal{H}|\mathcal{D}, \mathcal{I})$ describes exactly how much we should believe the various hypotheses.

Two problems with this approach: 1) we need to enumerate all possible hypotheses consistent with our prior information, 2) we need to compute $p(\mathcal{D}|\mathcal{I}) = \int p(\mathcal{H}|\mathcal{I}) p(\mathcal{D}|\mathcal{H}, \mathcal{I}) d\mathcal{H}$, which requires… enumerating all possible hypotheses consistent with our prior information.

Commentary part 1

If you start actually doing this, you’ll quickly notice that this is actually an impossible task in most useful cases. How many possible hypotheses are there about the coin? To begin with, the coin’s bias could conceivably take any real value between 0 and 1, which is an uncountable ‘number’ of hypotheses. We could bin these hypotheses together, if we - for all practical purposes - don’t care whether the coin has bias 0.50001 or 0.50002. Note that this is already an approximation to the true prescription of Bayes, just a rather inconsequential one.

Alright, so what else should be in our hypothesis space? Maybe the coin has two heads, maybe it lands on its side very often (we haven’t included this in the previous discussion of coin bias!), maybe the coin is fair, but not the person flipping it (an extra entity in the hypothesis?), maybe I’m hallucinating and there is no coin.

Does that last one even count as an hypothesis about the coin? Well, there are definitely observations imaginable that make such an hypothesis intuitively more likely than most mundane coin-hypotheses: what if the coin changes colour and shape mid-flight? The purpose of inference is to, well, make correct inferences about the world, and this is rather difficult if we don’t include the hypothesis that describes the world correctly.

We could restrict ourselves to just making statements about the coin, but ignoring factors does not make their influence go away. Maybe the robot always makes the coin come up heads, but once in a while some cosmic radiation flips an important bit in its control system and now the coin comes up tails. An agent with an hypothesis space that just contains hypotheses for ‘coin bias’ would put a lot of probability mass on high biases - near 1.0 - for the coin. From the perspective of the agent this is indistinguishable from what is actually happening, so one could be satisfied with this. However, if we now put the robot in a lead(?)-encased room where cosmic radiation has a harder time penetrating, the ratio of heads to tails changes and the agent has no idea why (but it will of course dutifully update its posterior to put more probability density around the appropriate coin bias).

That said, often we don’t care to distinguish between the hypotheses ‘this coin has a bias near 1’ and ‘this coin is being flipped by a robot that is programmed to make it come up heads almost always, such that it appears to have bias near 1’. This is fine: this is an approximation.

We could even imagine some kind of hierarchical process: we first try to find out how often the coin comes up heads. After many observations our posterior is concentrated around hypotheses with very high bias. Satisfied that we have learned this, we now try to find out any extra details about the coin flipping process, and split our ‘high bias’ hypothesis into disjunct proposals such as ‘there is a robot flipping the coin’, ‘this is an optical illusion’, etc. We now continue observing, paying close attention to any hints that may help us distinguish these.

But we could have been doing this all along! We could have been keeping track of all these hypotheses from the start, and using any of these ‘hints’ garnered from the initial round of observations to already start distinguishing these new hypotheses. We’ve thrown away observational evidence: another approximation.

So yeah. It’s pretty difficult follow the prescribed recipe exactly for a coin. Now imagine doing this for anything interesting, such as a typical modern-day machine learning problem. More on this another time.

Commentary part 2

And there’s more rain on this parade, because I’ve skipped over another hard problem: actually specifying the prior correctly. It’s one thing to ‘know things about the world with some measure of uncertainty’, it’s another to translate this into specific priors $p(\mathcal{H}|\mathcal{I})$. More on this another time as well.

Objective Bayesian probability theory is a beautifully prescriptive philosophy of reasoning under uncertainty: all the rest is just commentary. Very, very difficult commentary, written in Martian, waiting to devour the unwary.

Turtles all the way down

Epistemic status: pattern matching.

Say we have some prior information $\mathcal{I}$ about, say, physics that constrains the possible outcomes of our coin flips. Perhaps we believe ourselves to be the aforementioned Bayesian with access to all relevant knowledge, and we aim to simply calculate the result deterministically. How certain are we of this?

Presumably we used Bayesian updating to get there, so our certainty in the certainty-hypothesis $\mathcal{H}$ is measured by our current (at time $t$) prior $p(\mathcal{H}|\mathcal{I})$, which is equivalent to a posterior $p(\mathcal{H}|\mathcal{D}, \mathcal{I})$ from the previous time we updated on some relevant data $\mathcal{D}$, with our previous prior knowledge $\mathcal{I}$ at time $t-1$. And this previous prior is the result of another update step at time $t-2$ with the prior knowledge we had then, etc.

It’s Bayesian updates all the way down! Our belief in anything - Bayes says - is the result of continuously updating on observational data, given some prior information. So what happens if we follow this train of thought all the way to where we had no prior information? Well, this to me appears to be The Problem of Induction. If we have no prior information about anything, how do we know what inferences to make? We don’t! This is also closely related to the no free lunch theorem, which states that averaged across all possible problems, any two optimisation algorithms (read: learning) will perform equivalently. If there is no prior information on the kinds of problems we expect to encounter, then we’re stuck. There is no learning without inductive bias.

Luckily, it does seem to be the case that the kind of problems we encounter have some kind of regularity to them, and evolution seems to have outfitted our brains with somewhat decent inductive biases for learning these regularities. See also Occam’s Razor.

When explicitly reasoning using Bayes' theorem, the trick is then to translate these regularities / this inductive bias / this prior information into actual priors $p(\mathcal{H}|\mathcal{I})$, which is one of hard problems mentioned previously. A nice tidbit is that one of the methods for doing this - the principle of maximum entropy - also gives us some results from statistical mechanics for free. More on this - you guessed it - another time.

Strictly speaking it might be better to call $\frac{p(B|A)}{p(B)}$ - rather than $p(B|A)$ - the new information, since the logarithm of this is in expectation equal to the mutual information $I(A;B)$ between $A$ and $B$: a measure for how much we learn about $A$ after observing $B$. ↩︎

As far as I know, this terminology only makes sense in the context of model selection (see for instance chapter 28.1 Occam’s Razor in David MacKay’s book Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms), and is very confusing otherwise. ↩︎